By: Manoj Kuppusamy

Have you ever had a canker sore?

Most people have, those annoying little white ulcers on the inside of your lip that seem to sting no matter what you do. A couple of years ago when I was suffering from a particularly bothersome sore, I mentioned it to my mother in passing, and I was intrigued when she said she had a solution. She sauntered over to the freezer, and pulled out a green box filled with curious looking brown balls. She only knew the name of the ball in our native Tamil language, (மாசிக்காய் masikai) but after brief internet exploration, I found that the English translation is “oak gall” or “oak-apple”.

The galls were no bigger than a marble, and they had the appearance of a round nut, similar to an acorn, with small spiky nibs around the circumference. She split a gall in half with a pestle, and told me to go to sleep with the oak gall under my lip, on top of the sore. I had some difficulty falling asleep with a foreign object in my mouth, but when I inspected the sore in the morning, I was in for a surprise. The gall was stuck to the canker sore, it seemed to have shrunk and was covered in a stringy white substance that created webs around my lip. I removed the gall, and found that the canker sore was enveloped in the same string. I was able to peel the white substance from the canker sore easily, and found that where there used to be a red inflamed ulcer, now there was nothing! My lip was back to normal, and the only reminder was a small scar on my inner lip that left within the next couple of days. The holistic remedy that my mother gave me worked, and really well at that!

After my experience with the healing properties of the oakgall I was intrigued with how it worked, and why this medicine wasn’t more popular. This piqued my curiosity, as I’m sure it piqued yours: what even is an oakgall?

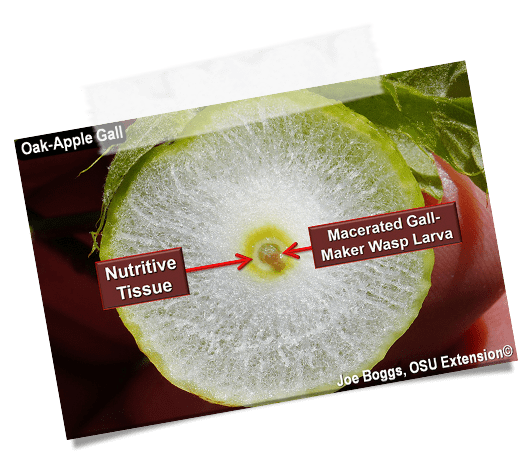

Oak galls, even though they look like a nut, are not nuts at all. In fact, they aren’t even something that oak trees make themselves, instead they are the result of a fascinating interaction between two different species!

First, lets examine how an oak gall is created. Female gall wasps, or gallflies, small insects similar in size to a fruit fly, will lay eggs on an oak leaf. Using its ovipositor (the egg-laying organ) the gall wasp injects chemicals that mimic the function of plant hormones, such as the growth hormone auxin, into the leaf tissue. The chemicals that the gall wasp injects cause the tree to react in a peculiar way: the leaf will curl around the eggs in the shape of a sphere. The abnormal tissue that now surrounds the egg-laying site is called a gall, and it provides both shelter and a food source for the larvae inside. Once the wasp larvae have completed their development, they pupate and eventually emerge as adult wasps boring holes in the gall in order to leave. Over time, the now empty gall will harden and become woody, providing a long-lasting record of the interaction between the oak tree and the gall wasp.

Now, how do these oak galls work to provide such immediate relief to canker sores? The answer lies within the peculiar chemical make up of these fascinating nests. Oak galls contain high concentrations of tannins, a naturally occurring chemical compound that is responsible for the dryness of wine, the strange dry feeling in your mouth after biting an unripe plum, and for curing leather. Tannins are astringent, which means they cause the shrinkage of body tissue. The high level of tannins in oakgalls mean that over time they will cause an ulcer to shrink and tighten to the point where the once inflamed skin is now less exposed.

So now the mysterious oak gall is less of a mystery to me. However, I will continue be amazed by its story, which starts with an oak tree and a tiny gall wasp and ends with a unique home remedy that I will be keeping in my freezer for the foreseeable future.

If you’re interested in reading more about galls and their real-world applications, check out this article.

Manoj Kuppusamy is a senior at the University of Pittsburgh majoring in Biology, where he is a research assistant at the Geriatric Psychiatry Neuroimaging Lab.

Leave a comment